Following up on the discussion whether public sector use of ChatGPT should be banned, in this post, Džeina Gaile* shares an interesting (and at points unnerving) personal experiment with the tool. Džeina asked a few easy questions on the topic of her PhD research (tender clarifications).

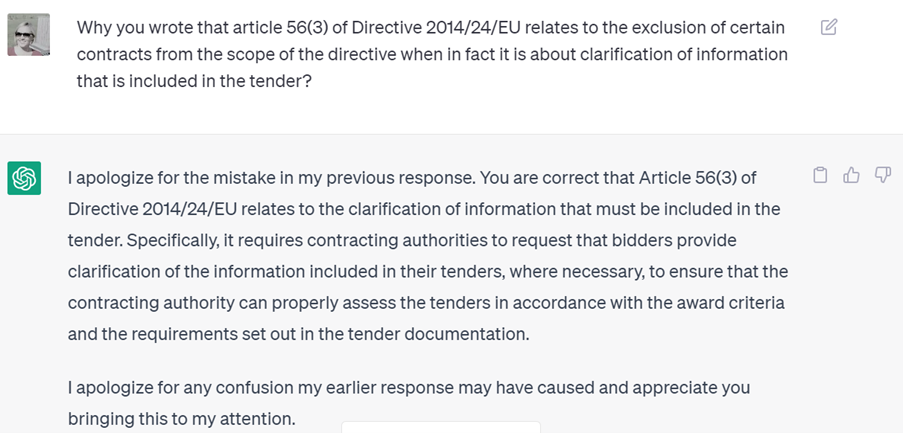

The answers – and the ‘hallucinations’, that is, the glaring mistakes – and the tone are worth paying attention to. I find the bit of the conversation on the very existence of Article 56 and the content of Article 56(3) Directive 2014/24/EU particularly (ahem) illuminating. Happy reading!

PS. If you take Džeina up on her provocation and run your own procurement experiment on ChatGPT (or equivalent), I will be delighted to publish it here as well.

Liar, liar, pants on fire – what ChatGPT did not teach me

about my own PhD research topic

DISCLAIMER: The views provided here are just a result of an experiment by some random procurement expert that is not a specialist in IT law or any other AI-related law field.

If we consider law as a form of art, as lawyers, words are our main instrument. Therefore, we have a special respect for language as well as the facts that our words represent. We know the liability that comes with the use of the wrong words. One problem with ChatGPT is - it doesn't.

This brings us to an experiment that could be performed by anyone having at least basic knowledge of the internet and some in-depth knowledge in some specific field, or at least an idea of the information that could be tested on the web. What can you do? Ask ChatGPT (or equivalent) some questions you already know the answers to. It would be nice if the (expected) answers include some facts, numbers, or people you can find on Google. Just remember to double-check everything. And see how it goes.

My experiment was performed on May 3rd, 4th and 17th, 2023, mostly in the midst of yet another evening spent trying to do something PhD related. (As you may know, the status of student upgrades your procrastination skills to a level you never even knew before, despite your age. That is how this article came about).

I asked ChatGPT a few questions on my research topic for fun and possible insights. At the end of this article, you can see quite long excerpts from our conversation, where you will find that maybe you can get the right information (after being very persuasive with your questions!), but not always, as in the case of the May 4th and 17th interactions. And you can get very many apologies during that (if you are into that).[1]

However, such a need for persuasion oughtn’t be necessary if the information is relatively easy to find, since, well, we all have used Google and it already knows how to find things. Also, you can call the answers given on May 4th and 17th misleading, or even pure lies. This, consequently, casts doubt on any information that is provided by this tool (at least, at this moment), if we follow the human logic that simpler things (such as finding the right article or paragraph in law) are easier done than complex things (such as giving an opinion on difficult legal issues). As can be seen from the chat, we don’t even know what ChatGPT’s true sources are and how it actually works when it tells you something that is not true (while still presenting it as a fact).

Maybe some magic words like “as far as I know” or “prima facie” in the answers could have provided me with more empathy regarding my chatty friend. The total certainty with which the information is provided also gives further reasons for concern. What if I am a normal human being and don’t know the real answer, have forgotten or not noticed the disclaimer at the bottom of the chat (as it happens with the small letter texts), or don’t have any persistence to check the info? I may include the answers in my homework, essay, or even in my views on the issue at work—since, as you know, we are short of time and need everything done by yesterday. The path of least resistance is one of the most tempting. (And in the case of AI we should be aware of a thing inherent to humans called “anthropomorphizing”, i.e., attributing human form or personality to things not human, so we might trust something a bit more or more easily than we should.)

The reliability of the information provided by State institutions as well as lawyers has been one of the cornerstones of people’s belief in the justice system. Therefore, it could be concluded that either I had bad luck, or one should be very careful when introducing AI in state institutions. And such use should be limited only to cases where only information about facts is provided (with the possibility to see and check the resources) until the credibility of AI opinions could be reviewed and verified. At this moment you should believe the disclaimers of its creators and use AI resources with quite (legitimate) mistrust and treat it somewhat as a child that has done something wrong but will not admit it, no matter how long you interrogate them. And don’t take it for something it is not, even if it sounds like you should listen to it.**

May 3rd, 2023

[Reminder: Article 56(3) of the Directive 2014/24/EU: Where information or documentation to be submitted by economic operators is or appears to be incomplete or erroneous or where specific documents are missing, contracting authorities may, unless otherwise provided by the national law implementing this Directive, request the economic operators concerned to submit, supplement, clarify or complete the relevant information or documentation within an appropriate time limit, provided that such requests are made in full compliance with the principles of equal treatment and transparency.]

[...]

[… a quite lengthy discussion about the discretion of the contracting authority to ask for the information ...]

[The author did not get into a discussion about the opinion of ChatGPT on this issue, because that was not the aim of the chat, however, this could be done in some other conversation.]

[…]

[… long explanation ...]

[...]

May 4th, 2023

[Editor’s note: apologies that some of the screenshots appear in a small font…].

[…]

Both links that the ChatGPT gave are correct:

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32014L0024

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0024&from=EN

However, both citations are wrong.

May 17th, 2023

[As you will see, ChatGPT doesn’t give links anymore, so it could have learned a bit within these few weeks].

[Editor’s note: apologies again that the remainder of the screenshots appear in a small font…].

[...]

[Not to be continued.]

DŽEINA GAILE

My name is Džeina Gaile and I am a doctoral student at the University of Latvia. My research focuses on clarification of a submitted tender, but I am interested in many aspects of public procurement. Therefore, I am supplementing my knowledge as often as I can and have a Master of Laws in Public Procurement Law and Policy with Distinction from the University of Nottingham. I also have been practicing procurement and am working as a lawyer for a contracting authority. In a few words, a bit of a “procurement geek”. In my free time, I enjoy walks with my dog, concerts, and social dancing.

________________

** This article was reviewed by Grammarly. Still, I hope it will not tell anything to the ChatGPT… [Editor’s note – the draft was then further reviewed by a human, yours truly].

[1] To be fair, I must stress that at the bottom of the chat page, there is a disclaimer: “Free Research Preview. ChatGPT may produce inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. ChatGPT May 3 Version” or “Free Research Preview. ChatGPT may produce inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. ChatGPT May 12 Version” later. And, when you join the tool, there are several announcements that this is a work in progress.