I had the great pleasure of giving a talk on the Catalan conflict and its fit within the Spanish constitutional framework within the Bristol Student Law Conference Lecture Series yesterday. These are the slides of the talk, updated to 30 October 2017 3pm, and a voice recording is available on demand. If you are interested, please email me at a.sanchez-graells@bristol.ac.uk.

Unacceptable pull back of Erasmus grants in Spain

The Spanish government has decided to change the rules applicable to Erasmus funding for exchange students midway the academic year. It has now announced a cut in its contribution to the Erasmus fund that will leave thounsands of Spanish students currently enrolled in programmes abroad without funding that had been pre-approved (see the coverage by The Guardian).

In my view, this is a myopic measure that breaches the most basic guarantee of legal certainty and legitimate expectations. It also shows a significant disregard for one of the most popular mechanisms of development of a true European demos and one of the more palpable examples of the potential implications of the European Citizenship enshrined in Article 20 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Deplorable!

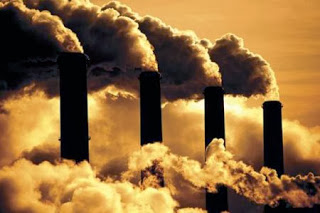

Not a gold pot: Free allocation of greenhouse gas emission allowances in Spain (C-566/11)

In its Judgment of 17 October 2013 in Joined cases C-566/11, C-567/11, C-580/11, C-591/11, C-620/11 and C-640/11 Iberdrola and Gas Natural, the Court of Justice of the EU has analysed and upheld a Spanish system whereby the remuneration of electricity production was reduced by an amount equivalent to the value of the emission allowances allocated free of charge to electricity producers in accordance with the 2005-2007 National Allocation Plan.

In its Judgment of 17 October 2013 in Joined cases C-566/11, C-567/11, C-580/11, C-591/11, C-620/11 and C-640/11 Iberdrola and Gas Natural, the Court of Justice of the EU has analysed and upheld a Spanish system whereby the remuneration of electricity production was reduced by an amount equivalent to the value of the emission allowances allocated free of charge to electricity producers in accordance with the 2005-2007 National Allocation Plan.

The rationale of the system (which actually manipulates/adjusts downwards the energy prices resulting from the Spanish wholesale electricity market) had been clearly spelled out by the Spanish executive, which clearly indicated that, given the fact that electricity producers opted for the incorporation as an additional production cost of the value of the emission allowances allocated free of charge, those prices needed to be adjusted to prevent an unfair enrichment or double whammy by energy producers.

In terms of Royal Decree-Law 3/2006, it was indeed justified to

[take] into account of the value of the [emission allowances] in the formation of prices in the wholesale electricity market is intended to reflect [that integration] by reducing, by equivalent amounts, the remuneration payable to the generating units concerned. Furthermore, the sharp increase in tariff deficit during 2006 makes it advisable to deduct the value of the emission allowances for the purposes of determining the amount of that deficit. The existing risk of high prices in the electricity-generation market, with their immediate and irreversible negative effects on end-consumers, justifies the urgent adoption of the provisions laid down in the present measure and the exceptional nature of those provisions (C-566/11 at para 17).

It is clear to see that, ultimately, the decision was aimed at avoiding a double transfer of resources to energy producers from the general budget and from consumers through tariff deficit compensation charges: first, by allocating emission allowances for free [which could then be immediately traded in the corresponding market or used as collaterial in financial deals; see Martín Baumeister & Sánchez Graells, (2012) "Algunas Reflexiones en Torno a Las Garantías Pignoraticias Sobre Derechos de Emisión de Gases de Efecto Invernadero y Su Ejecución" Revista de Derecho Bancario y Bursátil 127: 191-210] and, secondly, by also compensating higher tariff deficits (inflated) by the integration of the (non-zero, commercial) value of those emission rights in the wholesale energy prices.

However, the Spanish Supreme Court harboured doubts on the compatibility of this mechanism with Directive 2003/87. Indeed, according to the Tribunal Supremo, those measures could have the effect of neutralising the ‘free of charge’ nature of the initial allocation of emission allowances and undermining the very purpose of the scheme established by Directive 2003/87, which is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by means of an economic incentive mechanism (C-566/11 at para 23).

In my view, the analysis that the CJEU carries out in order to analyse this complicated situation must be praised, both for its clarity and brevity:

33 The Spanish electricity producers in question have incorporated, in the selling prices that they offer on the wholesale electricity market, the value of the emission allowances, in the same way as any other production cost, even though those allowances had been allocated to them free of charge.

34 As the referring court explains, that practice is undoubtedly cogent from an economic point of view, in so far as an undertaking’s use of emission allowances allocated to it represents an implied cost, known as an ‘opportunity cost’, which consists in the income that the undertaking has forgone by not selling those allowances on the emission allowances market. However, the combination of that practice with the pricing system on the electricity generation market in Spain results in windfall profits for electricity producers.

35 It should be noted that the on-the-day electricity trading market in Spain is a ‘marginalist’ market in which all producers whose offers have been accepted receive the same price, that is, the price offered by the operator of the last production unit to be admitted to the system. Since, during the period concerned, that marginal price was determined by the offers from operators of combined gas and steam power plants – technology attracting free emission allowances – the incorporation of the value of the allowances into the selling prices offered is passed on in the overall market price for electricity.

36 Accordingly, the reduction in remuneration provided for in Ministerial Order ITC/3315/2007 applies not only to undertakings that have received emission allowances free of charge, but also to power plants that do not need allowances, such as hydroelectric and nuclear power plants, as the emission allowance value incorporated in the costs structure is passed on in the price for electricity, which is received by every producer active on the wholesale electricity market in Spain.

37 Furthermore, as can be seen from the documents before the Court, the rules at issue in the main proceedings take into account factors other than the quantity of allowances allocated: in particular, the type of power plant and its emission factor. The reduction in remuneration for electricity production provided for under those rules is calculated in such a way that it absorbs only the extra charged as a result of the opportunity costs relating to emission allowances being incorporated in the price. This is confirmed by the fact that the levy is not incurred where power plant operators sell allowances allocated free of charge on the secondary market.

38 Accordingly, the aim of the rules at issue in the main proceedings is not subsequently to impose a fee for the allocation of emission allowances, but to mitigate the effects of the windfall profits accrued through the allocation of emission allowances free of charge on the Spanish electricity market.

39 It should be noted, in that regard, that the allocation of emission allowances free of charge under Article 10 of Directive 2003/87 was not intended as a way of granting subsidies to the producers concerned, but of reducing the economic impact of the immediate and unilateral introduction by the European Union of an emission allowances market, by preventing a loss of competitiveness in certain production sectors covered by that directive (C-566/11 at paras 33-39, emphasis added).

The CJEU recognises that, somehow, the Spanish price adjustment mechanism anticipates a correction which introduction was necessary in the revision of Directive 2003/87/EC:

insufficient competitive pressure to limit the extent to which the value of emission allowances is passed on in electricity prices has led electricity producers to make windfall profits. As can be seen from recitals 15 and 19 to Directive 2009/29, it is in order to eliminate windfall profits that, with effect from 2013, emission allowances are to be allocated by means of a full auctioning mechanism (C-566/11 at para 40).

Moreover, the CJEU stresses what, indeed, is the key to this case and, ultimately, indicates the problem of using 'free market' arguments in regulated industries such as energy production, where (wholesale) markets are actually a mere fiction:

since, on the Spanish electricity generation market, a single price is paid to all producers and the end consumer has no knowledge of the technology used to generate the electricity that he consumes and the tariff for which is set by the State, the extent to which electricity producers may pass on in prices the costs associated with the use of emission allowances has no impact on the reduction of emissions (C-566/11 at para 57, emphasis added).

Finally, in a very congruent manner, the CJEU has ruled that

Article 10 of Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 October 2003 establishing a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community and amending Council Directive 96/61/EC must be interpreted as not precluding application of national legislative measures, such as those at issue in the main proceedings, the purpose and effect of which are to reduce remuneration for electricity production by an amount equal to the increase in such remuneration brought about through the incorporation, in the selling prices offered on the wholesale electricity market, of the value of the emission allowances allocated free of charge( C-566/11 at para 59).

In my view, this a valuable Judgment and one that stresses the new rationality of the allocation scheme implemented by Directive 2009/29. Moreover, it makes clear (indirectly) that Member States must avoid granting unfair advantages and subsidies (ie State aid) to energy producers as a result of the the way they operate their greenhouse gas emission allowances allocation mechanims.

Avoidance of EU #publicprocurement rules by artificial contract split triggers #reduction in cohesion funds for #Spain (T-384/10)

In its Judgment of 29 May 2013 in case T-384/10 Spain v Commission, the General Court of the EU (GC) has dismissed the appeal against a 2010 Commission Decision that reduced the contribution of the structural and cohesion funds to several water management infrastructure projects in Andalusia due to various infringements of the applicable EU public procurement rules.

In its audit of the execution of the project, the European Commission identified several infringements of the EU public procurement rules by the project management firm appointed by the Andalusian regional authorities (which was mandated by art 8(1) of Regulation 1164/94 to comply with public procurement rules due to the project being financed with EU funds).

More specifically, the Commission considered that some contracts had been illegally split in order to keep them below the value thresholds that trigger the application of EU public procurement rules, in others technical criteria had illegally required undertakings to prove they had prior experience in Spain (which constitutes a discrimination on the basis of nationality), or award criteria had illegally included 'average prices' rather than a sound economic assessment of the offers, recourse to negotiated procedures had been abused, mandatory time limits had not been respected, and the ban on negotiations after the award of the contracts had not been respected. All in all, indeed, the project seemed to be severely mismanaged in terms of public procurement compliance.

In view of such shortcomings and infringements, and considering that full cancellation of the funding would however be a disproportionate penalty, the European Commission decided to impose financial corrections that partially reduced the contribution of the EU funds to the water management infrastructure projects by between 10 and 25% of the original contribution.

Spain tried to counter the Commission Decision and justify the inexistence of the alleged infringements, but to no avail. The discussion before the GC mainly revolved around the issue of the artificial split of the contracts in order to exclude the application of the EU rules (which is discussed in paras 65-97 of T-384/10). In order to address this issue, the GC offers a recapitulation of the criteria applicable to the assessment of whether a complex project involves a single or several detachable works.

66 As a preliminary point, it should be recalled that, under Article 6, paragraph 4 of Directive 93/37, no work or contract may be split up with the intention of avoiding the application of that Directive. Moreover, Article 1, letter c) of the Directive defines the term "work" as the outcome of building or civil engineering works taken as a whole that is sufficient of itself to fulfil an economic and technical function. Therefore, to determine whether the Kingdom of Spain infringed Article 6, paragraph 4 of the Directive, it must be ascertained whether the subject of the contracts at issue was one and the same work in the sense of Article 1, letter c), of the Directive.67 According to the case law, the existence of a "work" within the meaning of Article 1, letter c) of Directive 93/37 must be assessed in light of the economic and technical function expected from the result of the works that are the object of the corresponding public contracts (judgments of the Court of 5 October 2000, Commission / France, C-16/98, ECR p. I-8315, paragraphs 36, 38 and 47, to October 27, 2005, Commission / Italy, C-187/04 and C-188/04, not published in the ECR, paragraph 27, of January 18, 2007, Auroux and Others, C-220/05, ECR p. I-385, paragraph 41, and of March 15, 2012, Commission / Germany, C-574/10, not published in the ECR, paragraph 37).68 Moreover, it should be noted that the Court has stated that, for the result of various works to qualify as 'work' within the meaning of Article 1, letter c) of Directive 93/37, it suffices that those meet either the same economic function or the same technical function (Commission / Italy, paragraph 67 above, paragraph 29). The verification of the economic identity and of the technical identity are thus alternative and not cumulative, as submitted by the Kingdom of Spain.69 Lastly, it should be noted that according to the case law, the simultaneity of the call for tenders, the similarity of the notices, the unity of the geographical framework within which tenders are called for and the existence of a single contracting entity constitute additional evidence that can support the finding that different works contracts actually correspond to a single work (see, to that effect, Commission / France, paragraph 67 above, paragraph 65). [T-384/10 at paras 66-9, own translation from Spanish].

It is also worth stressing that the GC confirms prior case law and clarifies that there is no need to prove any intention on the part of the contracting authorities in order to find that they have infringed the rules against the artificial split of the contracts. In that regard,

94 Finally, the Kingdom of Spain argues that, in order to declare the existence of an infringement of Article 6, paragraph 4 of Directive 93/37, the Commission should have tested the concurrence of a subjective element, namely, the Spanish authorities' intention to split the contracts in question for the purpose of evading the obligations of the Directive. This argument cannot be accepted.95 In that regard, suffice it to note that the finding that a contract has been split in contravention of EU rules on public procurement does not require a prior demonstration of a subjective intent to avoid the application of the provisions contained in these regulations (see, to that effect, Commission / Germany, paragraph 67 above, paragraph 49). When, as in this case, such a finding has been proven, it is irrelevant to assess whether or not the infringement results from the will of the Member State to which it is attributable, from its negligence, or even from technical difficulties that it had to face (see, to that effect, the Court of Justice of October 1, 1998, Commission / Spain, C-71/97, ECR p. I-5991, paragraph 15). In addition, it must be remembered that, in the judgment in Commission / France and Auroux and Others, cited in paragraph 67 above, in order to declare the existence of an infringement of Article 6, paragraph 4 of Directive 93/37, the Court saw no need for the Commission to previously prove the intention of the member State concerned to avoid the obligations imposed by the Directive by splitting the contract. [T-384/10 at paras 94-5, own translation from Spanish].

The case also discusses the issue of the cross border interest of some of the contracts that, even after the prior criteria against the artificial split of contracts were applied, remained below the EU procurement thresholds. The considerations of the GC revolve basically around the fact that the works were to be conducted very close to the Portuguese border and, consequently, their cross-border interest cannot be excluded.

Once this is found, the inclusion of discriminatory technical criteria requiring undertakings to prove they had prior experience in Spain (and, even more precisely, in Andalusia and with the specific contracting entity) shows too clearly the discriminatory design of the procurement procedures and the ensuing breach of the EU public procurement rules (in this case, the general principles applicable to tendering of contracts not covered by the Directive).

In view of all such infringements, the GC confirms the adequacy of the financial adjustments imposed by the European Commission, without finding any fault in the fact that they were determined as lump sums proportional to the initial value of the contribution by the EU funds.

In my opinion, the Judgment in Spain v Commission does not create new law in this area, but it provides clarification (particularly on the fact that single works can constitute a technical or an economic unit, at para 68) and useful guidance on the criteria applicable in the assessment of compliance with EU public procurement rules in the tendering of large and complicated infrastructure projects, which should be welcome.

#CJEU pushes for EU single fiscal territory in ban of Spanish 'cross-border' tax on unrealised capital gains (C-64/11 Commission v Spain)

In its Judgment of 25 April 2013 in case C-64/11 Commission v Spain (press release), the Court of Justice of the EU has pushed for the further consolidation of the EU single fiscal territory by preventing any discriminatory tax treatment between companies that transfer their place of residence inside a Member State (domestic transfer) and those that transfer it to another EU Member State (EU transfer).

In the case at hand, Spanish corporate taxation law makes unrealised capital gains form part of the basis of assessment for the tax year, where the place of residence or the assets of a company established in Spain are transferred to another Member State. This rule has been challenged by the Commission as a restriction of freedom of establishment in that it puts the companies which have exercised that freedom at a cash-flow disadvantage.

The CJEU has indeed found that the immediate taxation of unrealised capital gains on the transfer of the place of residence or of the assets of a company established in Spain to another Member State amounts to a restriction on the freedom of establishment since, in such cases, a company is penalised financially as compared with a similar company which carries out such transfers in Spanish territory--in respect of which capital gains generated as a result of such transactions do not form part of the basis of assessment for corporate taxation until the transactions are actually carried out.

The CJEU has struck down such restriction as disproportionate in considering that Spain could preserve its powers in taxation matters by means of measures which are less harmful to the freedom of establishment. The CJEU considers it possible, for example, to request payment of the tax debt following the transfer, at the point at which the capital gains would have been taxed if the company had not made that transfer outside of Spanish territory. Moreover, the mechanisms of mutual assistance which exist between the authorities of the Member States are sufficient to enable the Member State of origin to assess the veracity of declarations made by companies which opt to defer payment of the tax. Thus, the Court clearly finds that the right to the freedom of establishment does not preclude capital gains generated in a territory from being taxed, even if they have not yet been realised, but it does preclude a requirement that that tax be paid immediately.

In this Judgment, the CJEU is clearly pushing for a suppression of tax borders within the EU and for an effective treatment of corporate changes of residence within the single market as domestic transfers. The CJEU strongly relies on the effectiveness of the current mechanisms of administrative cooperation in the field of taxation (as sufficient to enable Member States to exercise effective monitoring of transferred companies). These cooperation mechanisms (timidly created in 1977 by Council Directive 77/799/EEC) were revamped in 2011 by means of Council Directive 2011/16/EU and its Implementing Regulation 1156/2012.

Directive 2011/16 had to be transposed into national laws by 1 January 2013 but, as of today, several Member States have not yet communicated any implementing measures to the Commission--including Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Italy, Hungary, Poland and Portugal. This means that Member States need to get up to speed and effectively implement measures of administrative cooperation in tax matters if they want to keep (or improve) the effectiveness of their tax systems in the (growing) EU single fiscal territory.

As indicated in Directive 2011/16, Member States need to use their 'power to efficiently cooperate at international level to overcome the negative effects of an ever-increasing globalisation on the internal market'. Surely, developments and best practices generated in this inter-institutional cooperation setting will be relevant in the (likely?) future creation of a single EU tax authority.

#publicprocurement in price regulated markets: you cannot have your cake and eat it too, Mme. Spanish Minister of Health

The Spanish press has just reported that the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality has mandated some pharmaceutical companies to lower the prices of certain common use drugs. This would not be in the news but for the important detail that the Ministry has adopted this decision in retaliation for the low bids submitted by those pharmaceutical companies in a centralized procurement process run by the Andalusian Health Department in 2012 (which re-run is currently taking place).

The Spanish Health Minister was upset to see that, as a result of the centralized purchase of drugs, the Andalusian regional authorities were receiving better offers than the Ministry and other (regional) Health Authorities had managed to secure from the same pharmaceutical companies. Moreover, the prices offered in the Andalusian tender were significantly lower than those charged in the 'private' market to users whose medication is not covered by Social Security.

Instead of learning the proper lessons and exploring the potential benefits of more efficient procurement techniques (which remain to be seen in the long run, particularly in terms of sustainability of low prices, rate of innovation, protection of effective competition, etc--of which I am personally highly skeptical), the Ministry adopted a rather childish and short-sighted strategy whereby it has sought to punish the drug manufacturers by damaging their revenue stream.

In today's reported decision, the Ministry is forcing the unruly pharma companies to lower their prices for the affected drugs to levels even lower than those offered in Andalusia. The Ministry can impose such a price reduction as part of its general regulatory powers. In my opinion, this is an enormous mistake. The use of price regulation powers as a poison pill against pharma companies that bid aggressively in public tenders is simply nonsensical.

The only message that pharma companies should take home is the following: never, ever again, compete on prices. Surely, in the immediate future, the safest position for pharmaceutical companies will be to always bid the maximum authorized price, in order to avoid a downward revision every time they offer a discount in a public procurement procedure. And, in order to protect their revenue stream, to then lobby the Ministry to protect (or raise) the level of authorized prices.

Could one think of a worse outcome in terms of effective market competition and efficiency of public procurement? I can't. But I am sure that the Spanish Ministry of Health may surprise me in the future...