In case there was any question on the importance and central role of public procurement for the uptake of artificial intelligence (AI) by the public sector (there wasn’t, though), two recent policy reports confirm that this is the case, at the very least in the European context.

AI Watch’s must-read ‘European landscape on the use of Artificial Intelligence by the Public Sector’ (1 June 2022) makes the point very clearly by reference to the analysis of AI strategies adopted by 24 EU Member States: ‘the procurement of AI technologies or the increased collaboration with innovative private partners is seen as an important way to facilitate the introduction of AI within the public sector. Guidance on how to stimulate and organise AI procurement by civil servants should potentially be strengthened and shared among Member States’ (at 26). Concerning guidance, the report refers to the European Commission’s supported process of developing standard contractual clauses for the procurement of AI (see here), and there is also a twin AI Watch Handbook for the adoption of AI by the public sector (25 May 2022) that includes a recommendation on procurement guidance (‘Promote the development of multilingual guidelines, criteria and tools for public procurement of AI solutions in the public sector throughout Europe‘, recommendation 2.5, and details at 34-35).

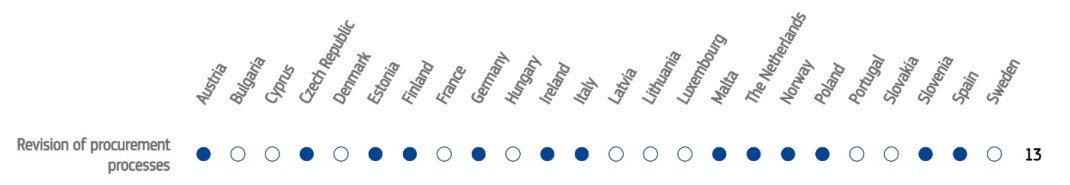

The European landscape report provides some more interesting detail on national strategies considering AI procurement adaptations.

The need to work together with the private sector in this area is repeatedly stressed. However, strategies mention that historically it has been difficult for innovative companies to work together with government authorities due to cumbersome procurement regulations. In this area, several strategies (12, 50%) [though note the table below indicates 13, rather than 12 strategies] come up with new policy initiatives to improve the procurement processes. The Spanish strategy, for example, mentions that new innovative public procurement mechanisms will be introduced to help the procurement of new solutions from the market, while the Maltese government describes how existing public procurement processes will be changed to facilitate the procurement of emerging technologies such as AI. The Dutch and Czech strategies mention that hackathons for public sector AI will be introduced to assist in the procurement of AI. Civil servants will be given training and awareness in procurement to assist them in this process, something that is highlighted in the Estonian strategy. The French strategy stresses that current procurement regulation already provides a lot of freedom for innovative procurement but that because of risk aversion present within public administrations all possibilities are not taken into consideration (at 25-26, emphasis in the original).

Own elaboration, based on Table 7 in the AI Watch report.

There is also an interesting point on the need to create internal public sector AI capabilities: “Some strategies say that the public organisations should work more together with private organisations (where the missing skillsets are present), either through partnerships or by procurement. On the one hand, this is an extremely important and promising shift in the public sector that more and more must move towards a networking perspective. In fact, the complexity and variety of skills required by AI cannot be always completely internalised. On the other hand, such partnerships and procurement still require a baseline in expertise in AI within the public sector staff to avoid common mistakes or dependency on external parties” (at 23, emphasis added).

Given the strategic importance of procurement, as well as the need to upskill the procurement workforce and to build additional AI capacity in the public sector to manage procurement process, this is an area of research and policy that will only increase in relevance in the near and longer term.

This same direction of travel is reflected in the also recent UK's Central Digital and Data Office ‘Transforming for a digital future: 2022 to 2025 roadmap for digital and data’ (9 June 2022). One of its main aspirations is to generate ‘Significant savings by leveraging government’s combined purchasing power and reducing duplicative procurement, to shift to a “buy once, use many times” approach to technology’. This should be achieved by the horizontal promotion of ‘a “buy once, use many times” approach to technology, including by making use of a common code, pattern and architecture repository for government’. Implicitly, this will also require a review of procurement policies and practices.

Importantly—and potentially problematically—it will also raise the stakes of AI procurement, in particular if the roll-out of the ‘bought once’ technology is rushed and its negative impacts or implications can only be identified once it has already been propagated, or in relation to some implementations only. Avoiding this will require very careful IA impact assessments, as well as piloting and scalability approaches that have strong risk-management systems embedded by design.

As always, this will be an area fun to keep an eye on.